Epic Bank Run: How the Second Largest Bank Failure in US History Happened in 48 Hours

Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) failed spectaculary this week. So, what happened?

How did you go bankrupt?

Two ways. Gradually, then suddenly.Ernest Hemingway

It was ready. All I had to do was schedule the newsletter to be sent at 10 am on Sunday. This week’s newsletter was supposed to be on how you could receive a 10% guaranteed return just by buying and holding 2-year US Treasuries. But then, the second largest bank failure in US history happened on Friday. So, I had to scrap everything and write about this shocking collapse. But you’ll see that the topic I wanted to write about is actually what is behind Silicon Valley Bank’s failure.

Bond Mechanics

To understand what happened to SVB, you must understand what bonds are and how they work. A bond is a type of debt issued by a government, a company, or the repackaging of hundreds of loans (usually mortgages) in the form of tradable security. Like stocks, bonds trade and have a market price.

There is one critical relationship you need to understand: When yields rise, the price of bonds falls. It is very bad for a bond investor when interest rates rise, as they have since early 2022. Why? Because if 18 months ago, you bought a $100, 10-year bond issued by the US Government that paid an annual coupon (i.e., interest rate) of 2% and that the same US Government is paying 4% on the 10-year bond it issues now, the price of the bond you hold must go down to offer a 4% yield despite only paying a 2% coupon. In this example, the price has to go down to $84. For $84, the buyer of this bond will receive a coupon of $2 every year (2% x $100) and $100 (par) in year 10.

What I am trying to say is that even if you will eventually get the $100 back from the US Government in ten years, if you need to sell the bond now, all you will receive from the market is $84.

Now that we have covered how bonds work, let’s review what happened to SVB.

The Bank of Venture Capitalists and Start-Ups

As you probably guessed from its name, many of SVB’s clients were start-ups. It was a great business to be in when money was pouring into tech in 2020 and 2021.

Between the end of 2019 and the end of 2022, SVB’s client deposits rose from $58 billion to $173 billion. It’s great, right? Not really. From a bank’s perspective, your deposits are a liability, and the bank needs to make loans or acquire assets that generate income with this cash. SVB had to do something with the money, and its clients were not taking many loans since most start-ups don’t generate positive cash flows and couldn’t repay loans.

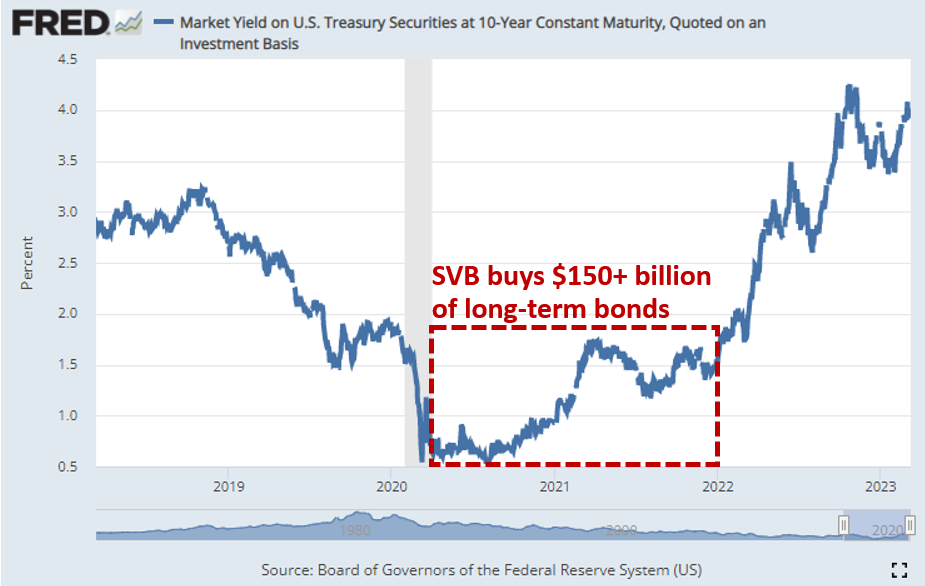

SVB ended up buying the type of assets it was allowed to buy: US Government bonds and Mortgage-Back Securities (MBS) guaranteed by the US Government. SVB bought $150+ billion of long-term, AAA-rated bonds with an average interest rate of 1.6%. They deployed this capital at the worst possible time.

Because the yield on long-term bonds rose from one to two percent in 2021 to four percent in early 2023, SVB was deeply underwater on its bond portfolio. But most investors and depositors were unaware of how bad the situation was because SVB did not have to report the fair market value of some of its holdings. Banking regulators allow banks not to report the fair market value of bonds if banks classify the bonds they own as “held to maturity.” The (questionable) logic is that if a bank doesn’t intend to sell a particular bond, it can claim it will eventually recover the $100 it is owed under this specific bond, even if the bond is currently trading at $80.

In summary, SVB financed the purchase of long-term bonds with customers’ deposits that could be withdrawn at any time. This strategy was as bad as it sounds.

The spark

On Wednesday, March 8, SVB disclosed it had taken a $1.8 billion loss on the sale of bonds and was trying to raise $2.25 billion in additional capital. The next day (Thursday), depositors initiated $42 billion in withdrawals. One day later (Friday), the bank failed and was seized by the California regulator. This was a textbook bank run.

Regulators in Washington DC knew very well about risks in the banking sector. In a speech given on March 6, just four days before SVB failed, FDIC Chairman Martin Gruenberg gave a speech at the Institute of International Bankers:

The current interest rate environment has had dramatic effects on the profitability and risk profile of banks’ funding and investment strategies. First, as a result of the higher interest rates, longer-term maturity assets acquired by banks when interest rates were lower are now worth less than their face values. The result is that most banks have some amount of unrealized losses on securities. The total of these unrealized losses, including securities that are available for sale or held to maturity, was about $620 billion at yearend 2022. Unrealized losses on securities have meaningfully reduced the reported equity capital of the banking industry.

You read this right. The US regulator, which guarantees deposits at US banks up to $250,000 per depositor, knew very well that US banks were sitting on $620 billion of losses on their bond portfolios. Translation: Many US banks are insolvent, but we don’t know which ones.

Because SVB didn’t have to disclose the losses on its portfolio of securities classified as “held to maturity,” it was not clear to investors that the bank was already insolvent. Many analysts on Wall St recommended investors buy the stock.

After 2008, you would think that credit rating agencies would have gotten better at evaluating the creditworthiness of banks. You would think wrong. When it failed, SVB had a stellar credit rating from S&P and Moody’s.

What happens to the money deposited at SVB?

The FDIC took control of SVB on Friday, March 10. See the press release here. All deposits under $250,000 are fully insured by the FDIC, and depositors will have access to their deposits as early as Monday, March 13.

There is just one problem…

For companies and individuals with more than $250,000 deposited at SVB, here is how it will work per the FDIC press release: “The FDIC will pay uninsured depositors an advance dividend within the next week. Uninsured depositors will receive a receivership certificate for the remaining amount of their uninsured funds. As the FDIC sells the assets of Silicon Valley Bank, future dividend payments may be made to uninsured depositors.”

Unless SVB is acquired over the weekend by another bank that would guarantee the deposits, those who had more than $250,000 deposited at SVB will have to wait until the FDIC liquidates SVB’s assets before recovering a percentage of the deposits they had with SVB. This could have dramatic consequences for companies unable to make payroll because their money would be stuck with SVB.

Who is to blame?

Spectacular collapses like that of SVB usually have many causes. Here are some of the parties that can be blamed for SVB’s demise:

The US Federal Reserve for raising interest rates so quickly that it led to large losses in bond portfolios.

Banking regulators for allowing banks not to report the fair market value of some of their investments if they classified them as “held to maturity,” making it impossible to assess the financial position of banks.

SVB for buying long-duration assets with client deposits and not hedging the risk that interest rates may rise, which would generate large losses on its bond portfolio.

Venture Capital funds for telling the start-ups they financed to get their money out of SVB on Thursday, even though it was the rational thing to do once it became clear SVB was insolvent.

SVB for not diversifying its client base, which turned against the bank when many start-ups tried to get their money simultaneously.

What is next?

Expect announcements over the weekend regarding the future of SVB. The most likely scenario is that another major bank will acquire SVB with a backstop from the Federal Reserve. What regulators should seek to avoid is the risk that contagion spreads and that depositors start withdrawing their money from smaller banks and send it to one of the “too big to fail” banks like JP Morgan, Citi, Wells Fargo, and Bank of America.

The FDIC doesn't have nearly enough funding to cover deposits if many banks start failing at the same time. Fortunately, because deposits are in US Dollars, the Fed can always print more. It’s the magic of fiat currencies.

Even though the risk materialized in the US with SVB, there are other countries where banks are in much more precarious situations. Countries where banks bought bonds at zero interest rate, or worse, at a negative yield, for more than a decade…

Don’t be like SVB; remember a few basic principles of sound financial management:

Hold a diversified portfolio of assets.

Match the time horizon of your investments with your financial needs and objectives.

Do not hold all or most of your assets with a single entity. Make sure to have accounts at different banks, brokerage firms, and, if possible, in different jurisdictions.

Own assets you can self-custody (precious metals, crypto assets as long as you don’t leave them on any exchange).