How COVID-19 and Central Banks Made the Conversation About Bitcoin so Much Simpler

Bitcoin in the era of unprecendeted money printing

I have given presentations on Bitcoin many times over the years. Every time, I start with the same thing: a history of money. How human societies have used different forms of money over time: from things like shells, salt, rocks and then gold and paper backed by gold. All this to end with the current fiat currency system, in which we have been living since 1971, when Nixon suspended the convertibility of the US Dollar to a fixed quantity of gold. I always explain that more money can be created the central bank simply by printing (digitally these days) any quantity it wants. Yet, I always get a sense that people don’t quite either understand it or believe me. Then COVID-19 happened.

An Unprecedented Shock Led to an Unprecedented Response

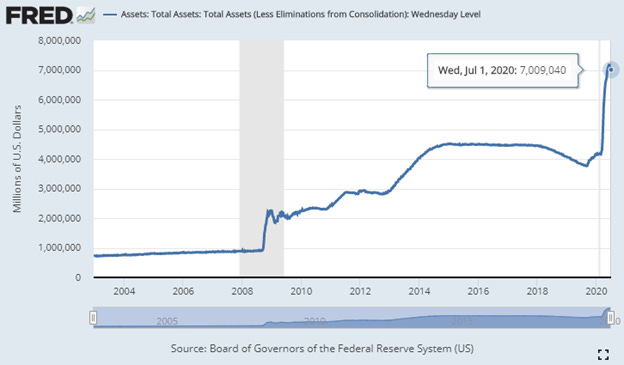

In response to the COVID-19 economic shock, governments and central banks of developed countries unleashed stimulus packages of unprecedented sizes. G20 countries have so far extended fiscal support estimated by CSIS at $7.6 trillion, equivalent to 11% of their GDP. In my home country, France, the government started paying the salaries of more than half of all private sector employees in April, half! In the US, the Fed printed more than $3 trillion to buy US Treasuries, Mortgage-Backed Securities, Investment Grade Corporate Bonds and even… Junk Bonds!

Suddenly I started receiving phone calls from friends and family all asking me the same question “Where is all this money coming from? Who is lending so much to the government?” Invariably, my answer was always the same: “it’s easy, central banks created the money governments needed”. Needless to say, I subsequently had a lot of explaining to do.

The Chairman of the Fed, Jay Powell, even went on TV to explain what the Fed was doing to support the economy.

Before him, Ben Bernanke, who was Chairman of the Fed before Jay Powell and Janet Yellen, had given pretty much the same explanation years ago.

Fiat currency is an odd animal: you and me have to work to earn it, but a few people on the planet just need to press a few buttons to create as much as they want. While most people have heard about what happened to the currencies of Germany in the 1920s or Zimbabwe and Venezuela more recently, few actually realize that the principles of all fiat currencies are identical everywhere.

The chart below, which illustrates the US Dollar money supply (M2) over the past 40 years, shows that the acceleration in the creation of US Dollars we are witnessing since March is unprecedented.

Since March, what the Fed printed corresponds to the equivalent of a full year of tax revenues of the US Federal Government. If the Fed can just print what is needed to run the US Federal Government without any adverse consequences, then why have taxes at all? This is what proponents of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) have been saying for a while now: in a world without inflation, why not just print the money you need to run governments instead of taxing citizens and companies? Seems to good to be true? Well it’s because it probably is. History has proven that it never works and that sooner or later, inflation always rears its ugly head…

Where Bitcoin (and Gold) Comes In

With yields of government bonds of OECD countries getting very close to zero or already being in negative territory, there are fewer and fewer places left to protect assets against the (virtual) printing presses of central banks. While gold has been the #1 choice for thousands of years, it may be time to consider Bitcoin as a complement.

“Gold is money, everything else is credit”

JP Morgan testimony to US Congress in 1912

Bitcoin has a fixed supply that is already known and set by immutable code: there can never be more than 21 million bitcoins. To date, 18.4 million bitcoins have already been mined, or 88% of all bitcoins that will ever be mined. Since the last halving in May this year and for the next four year, we know that only 6.25 bitcoin will get mined every 10 minutes, or 328,500 per annum, which corresponds to an annual inflation rate of the Bitcoin Supply of 1.7%. After four years, the number of new bitcoins mined every 10 minutes will be halved, and the process will repeat every four years. In comparison, the US Dollar Money Stock (M2) has grown by a staggering 25% over the past 12 months alone.

While the cap on the Bitcoin supply has always been there, this feature is all the more attractive now that central banks are printing money at a furious pace.

When the stock of money grows faster than the GDP, the result is inflation. So far, inflation has been concentrated in asset markets (stock market and bond market). With the IMF now predicting a contraction of the GDP of advanced economies of 8% in 2020, however, the risk of severe disconnect between the growth of the money stock and that of the economy has never been greater in recent decades. This cannot end well.

The Race for Scarce Assets is On

Bitcoin is just 11 years old, it is ruled by code, and despite facing competition from thousands of other cryptocurrencies and countless forks, its market capitalization is north of $150 billion and it accounts for more than 60% of the market capitalization of all cryptocurrencies. It is, with gold and long term US Treasuries, among the best performing assets this year. Yet, it is still tiny compared to the gold and US Treasuries markets, which are $10 trillion and $20+ trillion respectively, making the potential risk/reward ratio of Bitcoin very attractive.

Bitcoin’s volatility is still high and has deterred many investors from getting exposure to this asset, but whether it is ‘schmuck insurance’, as Chamath Palihapitiya, the billionnaire founder of Social Capital, likes to call it or a bet on the future of money, some Bitcoin exposure in a portfolio has never made more sense than now. With central banks printing money like there is no tomorrow, what if the real risk was not in owning some Bitcoin, but in not having any exposure to it?

The views and interpretations in this article are those of the author and do not represent the views of the World Bank.