The Schrödinger Risk

How time transforms the nature of investment risk, and what we can learn from Warren Buffett's 60-year experiment

If you don't find a way to make money while you sleep, you will work until you die.

Warren Buffett

In 1935, an Austrian physicist named Erwin Schrödinger came up with an idea that was both absurd and revolutionary. To challenge his colleagues' interpretation of quantum mechanics, he proposed a thought experiment in which a cat is placed in a sealed box with a radioactive atom. If the atom decays, it triggers a mechanism that releases poison, killing the cat. Until someone opens the box to check, the cat exists in a "superposition"—simultaneously alive and dead.

This wasn't Schrödinger's twisted fantasy but his way of demonstrating how quantum theory, when extended to everyday objects, leads to seemingly ridiculous conclusions. Little did he know that 90 years later, his unfortunate hypothetical feline would provide the perfect metaphor for a post on long-term investing.

Your investments exist in a similar quantum state of superposition. They are simultaneously risky and not risky. The wave function that collapses this duality into a single reality isn't observation — it's time.

Earlier this month, Warren Buffett announced his retirement from Berkshire Hathaway after 60 years at the helm. His investment career represents perhaps the greatest practical experiment in long-term investing the world has ever seen. And what did this experiment reveal? That the conventional understanding of risk is fundamentally flawed.

The Time Inversion of Risk

Every time I go home, my French friends inevitably ask me the same question: "Vincent, what can I invest in that has no risk?" I always respond with another question: "Over what time horizon?"

They look at me like I've asked something nonsensical. Risk is risk, isn't it? No. Risk transforms with time, like water changing states from solid to liquid to gas.

The supposedly "safest" investments — cash, money market funds, Certificates of Deposit, or for my French readers, your beloved Livret A and "fonds en euros à capital garanti" in your assurance vie — are actually guaranteed to lose purchasing power over time. There is indeed "no risk" as advertised — you are guaranteed to get poorer.

Meanwhile, assets considered "volatile" and "risky" in the short term — stocks, precious metals, Bitcoin — become progressively less risky as your time horizon extends. This is why the investment mix of my mother and that of my daughter should be very different.

This is the great inversion of risk. Cash is "safe" for a day but deadly over decades. Stocks are volatile day-to-day but remarkably reliable over decades. An investment can be both risky and not risky — it just depends on when you open the box.

It’s why I often joke I only keep in fiat (cash) what I can afford to lose! The opposite of what uninformed armchair financial analysts tell you, i.e., that you should only invest in volatile assets what you can afford to lose.

To illustrate this time inversion of risk empirically, I extracted nearly a century of S&P 500 returns since 1928 and created the chart below.

What you're looking at captures 90% of all possible outcomes at different holding periods, excluding only the extreme 5% on either end. Given enough time, the supposedly "risky" asset becomes the safe one. If you only invest for a year, you may experience high returns or severe downturns. But volatility shrinks dramatically as your holding period increases, eventually reaching a point where the worst outcomes become positive returns.

The supposedly "risky" stock market becomes the safe investment given enough time, while "safe" assets like cash become guaranteed losers to inflation and currency debasement. The same asset class can be both risky and safe. It all depends on your holding period.

Volatility: Risk for Those Who Don't Understand Risk

The finance industry has done us a tremendous disservice by equating volatility with risk. Volatility simply measures how much an asset's price bounces around. It tells you nothing about the probability of permanent loss or gain over meaningful time periods.

Let me offer an extreme example to make my point. Which would you rather have held over the past decade: Bitcoin or Argentine Pesos?

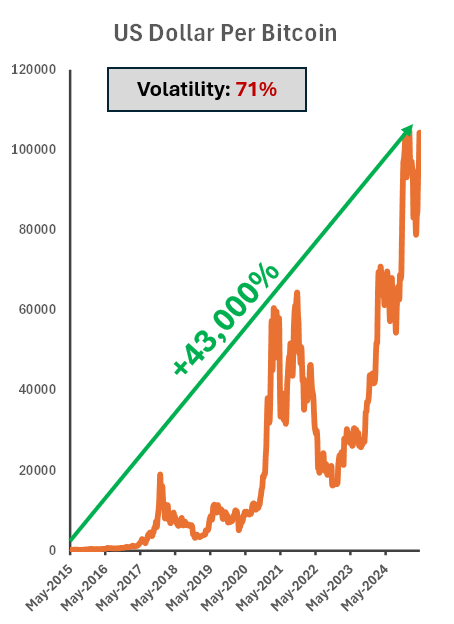

Bitcoin has been wildly volatile, swinging 20% in a matter of days or even hours. Meanwhile, the Argentine Peso has had much lower day-to-day volatility. But Bitcoin has increased in value by roughly 43,000% over the past decade, while the Argentine Peso has lost 99% of its value against the US Dollar.

The volatility of Bitcoin over the period was 71%, while that of the Argentine Peso was “only” 24%. But there shouldn’t be any disagreement on which was the better of the two to own.

If you choose short-term "stability," you choose long-term erosion of your wealth. If you tolerate volatility, you choose potential prosperity.

The Risk-Return Formula

Now for a bit of financial theory. In its simplest form, the annual return R on an asset can be expressed as:

I can feel half my audience leaving already, but stay with me. This is actually quite simple: Return = Expected Return + Volatility, and volatility can be positive or negative.

The formula tells us something profound: you cannot have return without volatility. They are two sides of the same coin.

When people demand zero volatility on the right side of this equation, they necessarily sacrifice expected return on the left side. My French compatriots are particularly obsessed with having zero volatility in their portfolios, as I explored in my "Willing Inmates" newsletter. The psychological comfort of never seeing a down day, a down month, or (heaven forbid) a down year comes at the extraordinary cost of long-term returns.

Volatility exists because there is disagreement about the future value of an asset. If there was perfect agreement, there would be no volatility—and also no excess return above the risk-free rate. The very disagreement that creates volatility creates the opportunity for return.

For someone with a low time preference like me, cash is the riskiest asset. I know with absolute certainty it will be worth less in 10 years. With stocks, gold, or Bitcoin, I don't know exactly what they'll be worth, but I believe I have a much higher probability of preserving and growing my wealth with them than with “risk-free” investments.

Diversify Human and Financial Capital

Your investment strategy shouldn't exist in isolation from your career. They are two forms of capital—human and financial—that should complement rather than mirror each other.

If you have a stable job with steady income that's relatively recession-proof (government employee, tenured professor, healthcare professional), you can afford to take more risk with your financial capital. Your human capital acts as a bond-like asset in your overall portfolio. Limited to nonexistent upside, but downside protection.

Conversely, if your income is highly variable or at risk during economic downturns (sales, real estate, startup employee), you should probably pursue more stability in your investment portfolio. Your human capital already has equity-like risk characteristics, with a potentially high upside but no downside protection.

Your ability to withstand market drawdowns is directly tied to your job stability and short-term cash needs. If you know your income is secure and you won't need to tap your investments for many years, market volatility becomes merely theoretical—numbers on a screen rather than an actual threat to your financial security.

Ironically, this wisdom is usually inverted in practice. Tenured professors cling to "safe" government bonds while startup employees YOLO their savings into meme stocks and crypto moonshot!

Don't Trade. Let Compounding Work Its Magic

Warren Buffett didn't become one of the richest people in the world by frantically trading in and out of positions or timing market tops and bottoms. He identified good businesses, bought them at reasonable prices, and let time do the heavy lifting.

"The stock market is a device for transferring money from the impatient to the patient" Warren Buffett

Those who sold during last month's panic are now watching the market approach new all-time highs without them. If market volatility and emotions drove your decision-making, you need to revisit your asset allocation — it's clearly too aggressive for your risk tolerance.

Let me illustrate the power of compounding with Buffett's own track record. Over his 60-year tenure, his company, Berkshire Hathaway, achieved a 19.9% compounded annual return, compared to 10.4% for the S&P 500.

That doesn't sound like much difference, does it? Just about twice as good. But over 60 years, this translates into a 5.5 million percent return versus 39,000 percent for the S&P 500. Put another way, if Berkshire Hathaway went down 99% tomorrow, it would still have outperformed the S&P 500 over those 60 years.

A mere $10,000 invested in Berkshire Hathaway in 1964 would be worth approximately $550 million today. And here's the most mind-boggling part: 98% of Buffett's net worth was generated after he turned 65. Not because he suddenly became a better investor, but because he had close to 30 more years of compounding left at 65.

Even Buffett had down years. Even Buffett made mistakes. But he understood the Schrödinger nature of risk—that short-term volatility and long-term risk are entirely different animals.

Interestingly, Buffett is now sitting on a massive cash pile of nearly $350 billion. He's leaving it to his successor to deploy. No pressure!

Preparing for an Unknowable Future

None of us can predict the future. Not me, not you, not even Warren Buffett. But we can prepare for it by understanding the nature of risk across different time horizons and setting our asset allocation accordingly.

If you're young or have a long time horizon, embrace the risk of short-term volatility to avoid the much greater risk of long-term purchasing power erosion. If you're approaching retirement, gradually shift to reduce volatility—not because volatility itself is bad, but because your time horizon is shortening.

Above all, understand that risk exists in a quantum state. Your job is not to eliminate it, you can’t, but to harness it in a way that aligns with your personal time horizon and goals.

The question isn't whether your investment is dead or alive when the box is closed; it's whether you have the patience to wait until the right time to look.

BONUS

Like most of my readers, I was first introduced to Schrödinger's cat through the TV series "The Big Bang Theory," so I could not resist sharing the original scene between Penny and Sheldon. Enjoy!

Nothing in this newsletter constitutes financial or investment advice. All content is provided for informational and entertainment purposes only. I'm just a guy with a keyboard, some AI assistants, and opinions about the economy—not your financial advisor. Financial markets are unpredictable, and any investments you make based on what you read here (or anywhere else) are entirely at your own risk. Always do your own research and consider consulting with a qualified financial professional before making significant investment decisions. Past performance of any asset mentioned is not indicative of future results. In short: if you make money based on something I wrote, it's because you're smart—if you lose money, that's definitely not on me.